Sound Signatures

- Categories Sound

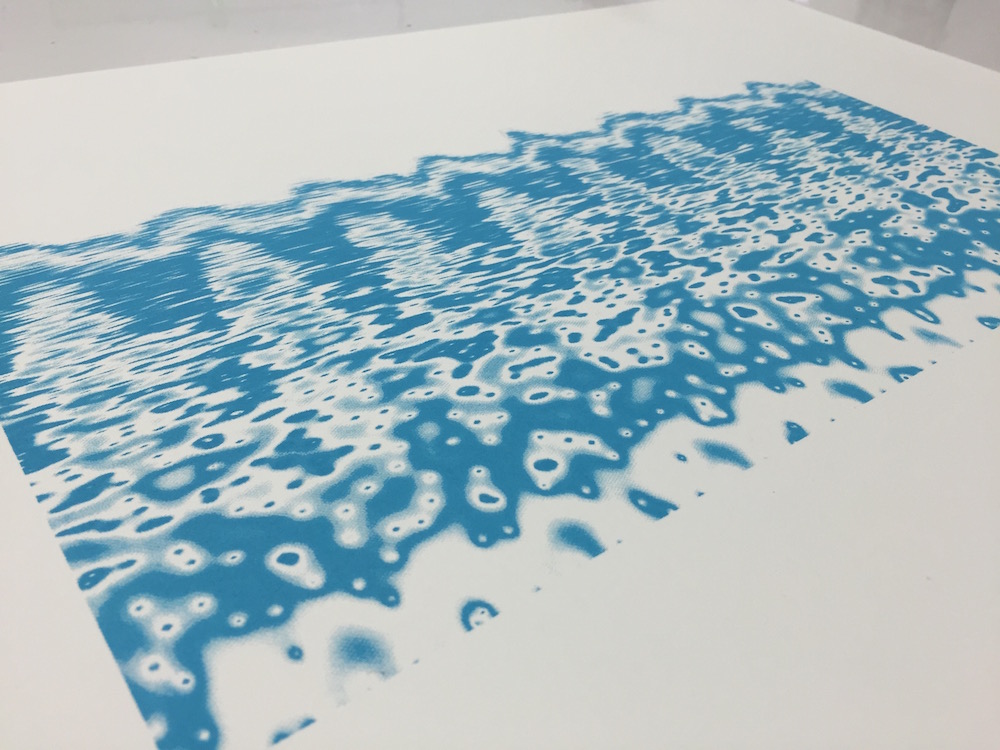

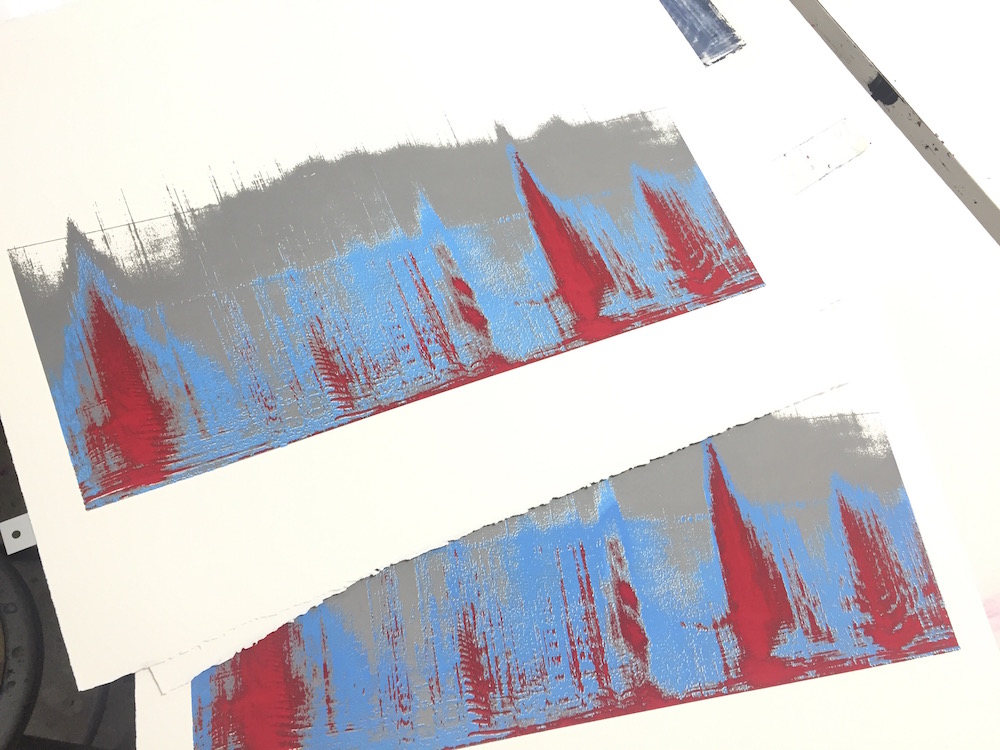

screen printed spectrogram, ‘Sound Signature’ series, P51 (WWII era fighter with Merlin engine)

In 2015 I spent two months at the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum in Washington DC, on an Artist Research Fellowship. My plan was to look at the sound of air travel, thinking about how sound is integrated into our associations and memories of planes, spacecraft, and technology in general.

This residency resulted in “Sound Signatures”, a series of screen prints of sound recordings of historical aircraft. You can buy some of the prints on my shop.

Being a Smithsonian Fellow opened up a lot of doors for me, allowing me behind-the-scenes access to a number of historical aircraft societies as well as archives and experts all up and down the east coast. I spent the first half of the residency travelling around making field recordings of extremely rare airplanes, from a Bleriot XI to a P51.

I’d especially like to thank the Old Rhinebeck Aerodrome, who were extraordinarily helpful and even put me up for the night after a wonderful visit.

These trips resulted in a large library of recordings – here’s a small selection:

Whilst editing and producing all the recordings I became really interested in seeing their spectrograms (a way of visualising the frequencies of a sound over time). Looking at the sounds this way revealed a number of hidden details, like the slight variations in the chugging of each cylinder, or the whistling of air rushing through the wires of a triplane.

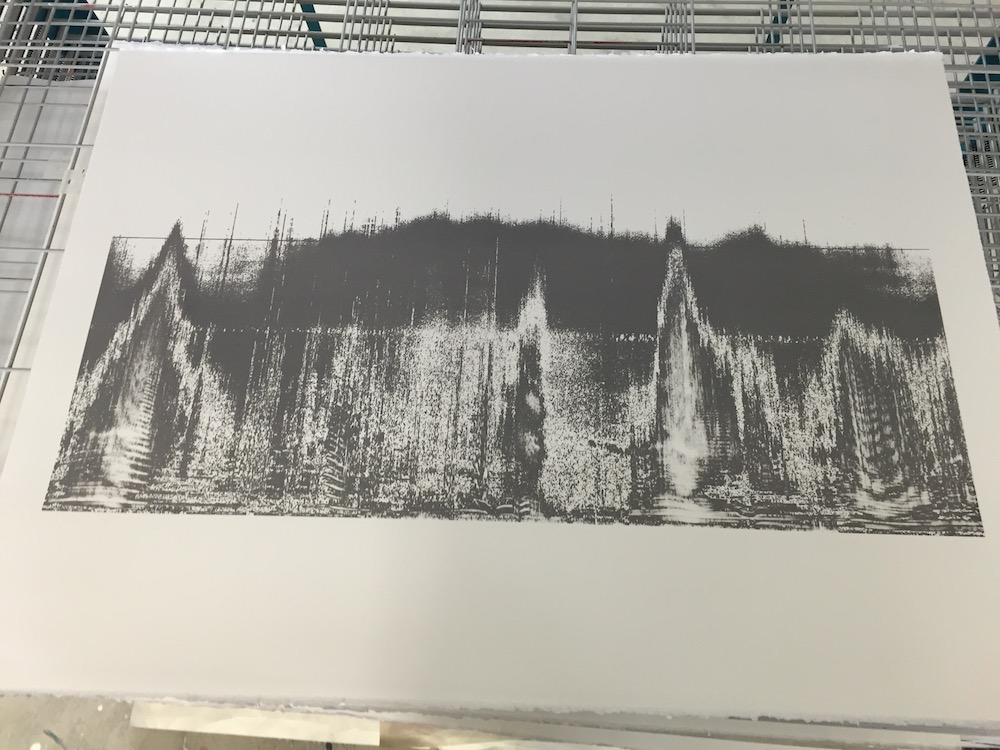

digital spectrogram of Fokker Dr1 flying around the aerodrome

Visualising sound has a long and fascinating history: the very first sound recording machines were only able to make pictures of sound, without playing them back. Recent research has enabled us to hear these early recordings again, as detailed in the wonderful book Pictures of Sound by Patrick Feaster. In a gruesome twist, some of these early recording machines used actual human ears as microphones, which I learned about at a great little exhibition at the Smithsonian American History Museum.

Having recently started doing a fair amount of screen printing, I got in touch with the Open Studio DC about doing some explorations with these spectrograms. Many thanks to Carolyn Hartmann for her enthusiasm and endless help – with her assistance I was able to produce a number of screen prints of the field recordings.

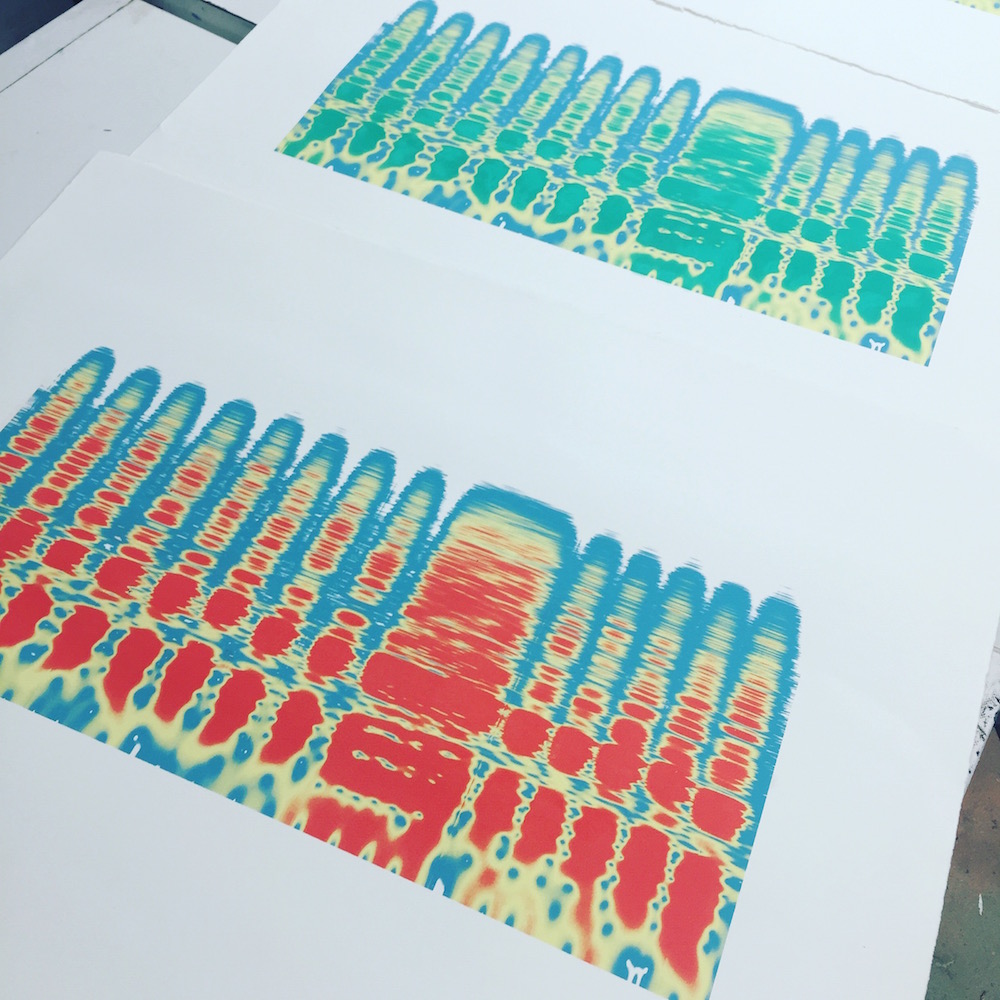

Fokker Dr1 spectrogram, screen printed on paper

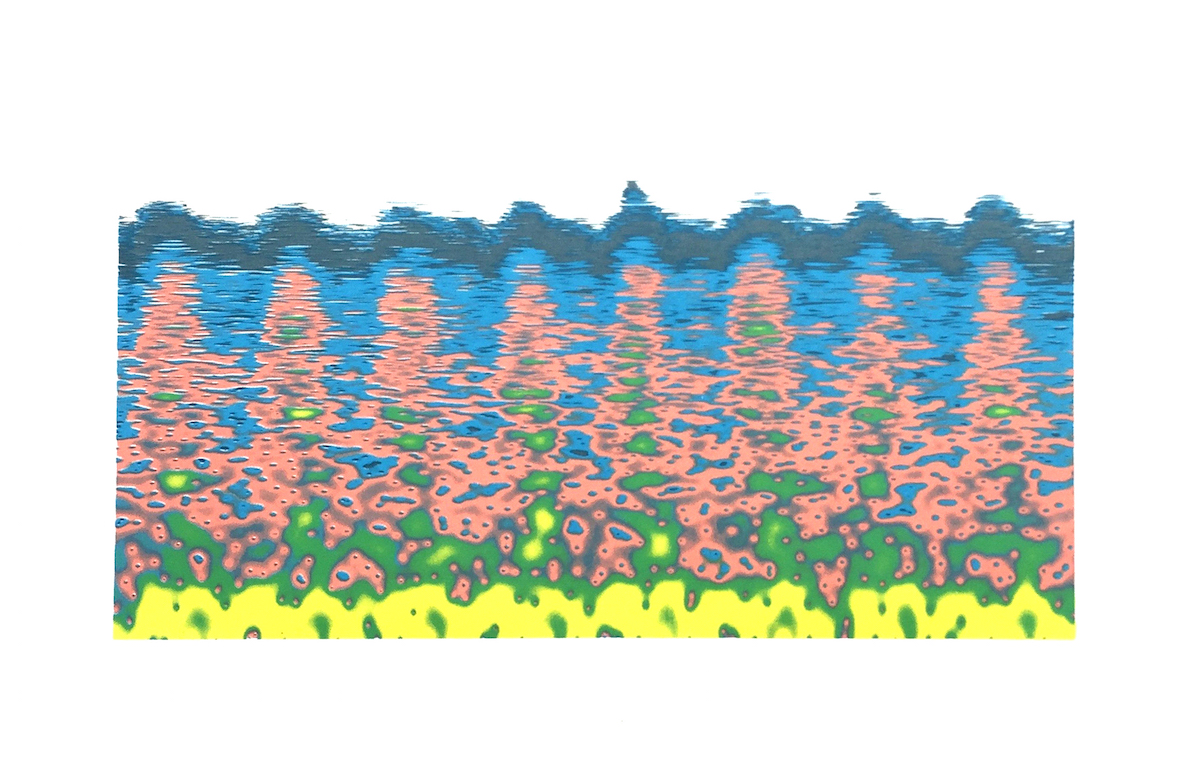

spectrogram of B24 idling with P51 flypast, three times digitally processed and printed on paper

Fokker D.VIII spectrogram printed on paper, two different versions

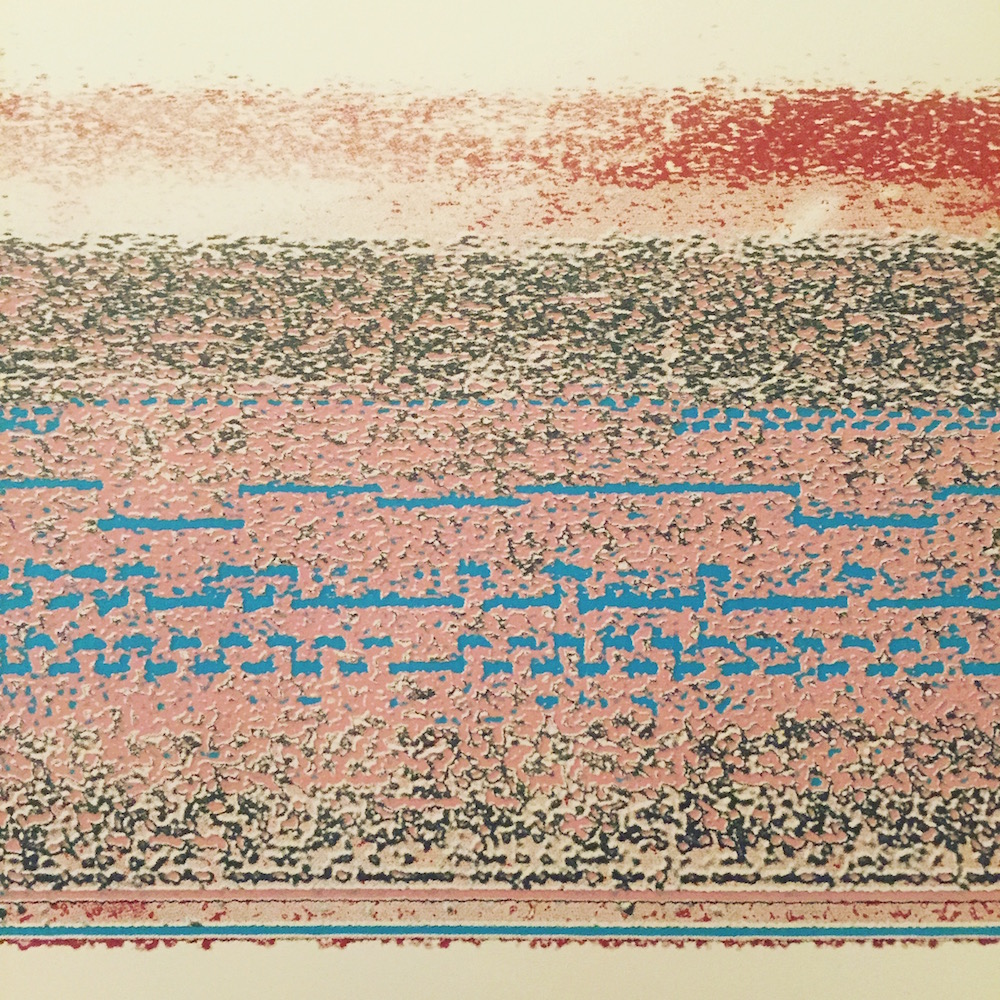

One of the things I love about screen printing is the amount of steps it places in between me, the artist, and the end result. For me, each step of the process became symbolic of the way that we remember sound, as a representation of an instantaneous moment that can not really be recreated. I was making a recording, editing it, creating a digital spectrogram, adjusting the colours, separating out the layers, choosing my inks, printing digital transparencies, exposing them onto a screen, and finally layering the inks together to create a deeply imperfect and flawed version of the original sound. Strangely, I found that deeply rewarding.

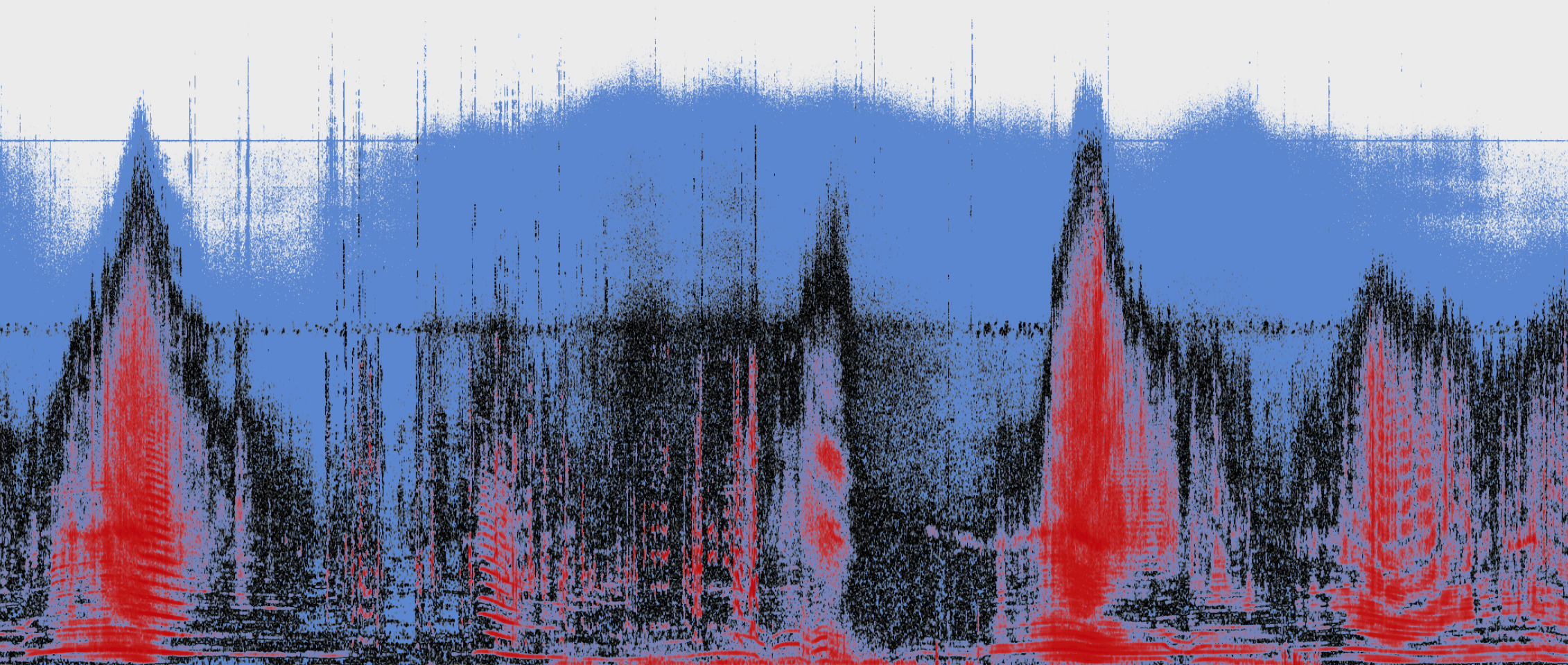

I was also lucky enough to get to listen to some archive reel-to-reel tapes in the museum archives. My favourite recordings were the satellite transmissions from the 1960s, which sounded like amazing electro-acoustic music. I took a bunch of those and turned them into a short piece called “Telemetry”.

You can clearly see the transmission frequencies in the screen printed spectrogram of one of these satellites.

Most of all I’d like to thank Roger Connor, who supported this residency and basically made it all happen, and Peter Manseau, who started the process for getting me involved. It was an amazing opportunity and I’m very pleased with the work that came out of it.